Hello bots! Social Media Automation Apps

An exploration of the most relevant automation apps available on Google Play store used as bots in a social media environmentTeam Members

Eloy Caloca Lafont and Gabriela Sued. Tecnológico de Monterrey, Mexico City CampusContents

Summary of Key Findings

- There is a high number of apps (over 200) aimed to automate social media practices like posting (or reposting), “liking” or adding friends, available for all kind of consumers at Google Play store. They are different for every social media platform.

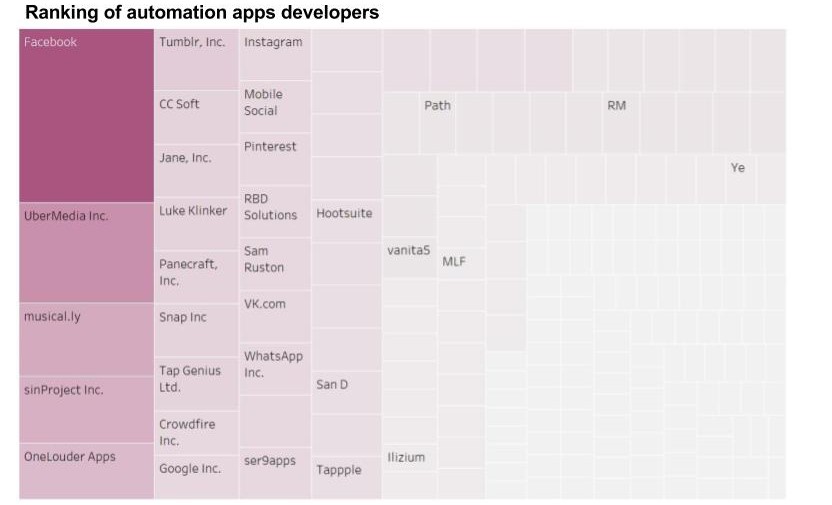

- Main developers of automation apps are large Internet companies: Facebook and UberMedia in the first places, Google, Tumblr and Instagram afterwards..

- Main automation apps related to Twitter are often used for political engagement activities in this platform.

- There is a considerable relationship between automation apps and anonymity. Social media bots can be related to ghost accounts.

- It is important to design a digital methods map to portray and systematize the detection, analysis and possible classification of automation apps and bots.

1. Introduction

In social media environments users interact with thousands of digital objects that reproduce or optimise their cultural practices. However, it is difficult to distinguish between publications, interchanges or messages originally produced by humans in real time and other ones generated automatically through devices created to post, write or spread contents instantly. Automation tools or software that allow accelerated activity on sociodigital platforms are known as bots. Bot is a short term for web robot: an application (app) that performs tasks or runs scripts over the Internet without previous direct inputs (Dunham & Melnick, 2008; Chu, Gianvecchio, Wang & Jajodia, 2012). Most bots are spiders used for web crawling or web indexing, which means systematic browsing of websites to update the contents or indices of a web or search engine, but in the case of social media sites as Facebook, Twitter or Instagram, bots may be downloadable or commercial apps that respond to the intentions of a user who programs or manipulates them to acquire public notoriety, to enforce a marketing plan, or to support or detract a political or ideological cause (Kollanyi, Howard & Wooley, 2016).

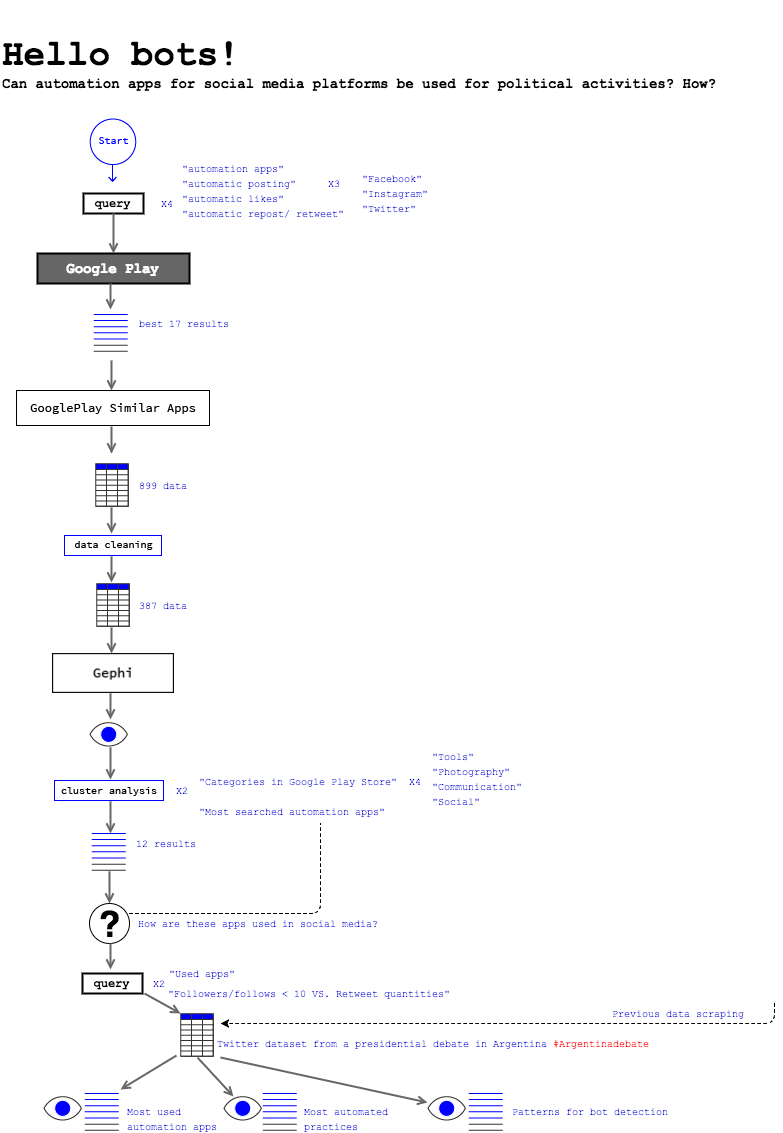

Despite 51.8 percent of all web traffic is made up of bots (Zeifman, 2017) academics still know little about their behavior. On this exploratory study we identified which apps available to anyone on Internet through Google Play store, the largest online platform to get over one million Android tools (Warren, 2013), are transforming human digital practices into automated interactions. Besides, this project aimed the final construction of a digital methods map: a flowchart of our reflections, activities and products for anyone interested in the detection of social media bots using our methodology.2. Initial Data Sets

As a starting point, we decided to work with a sample of downloadable or commercial social media automation apps considering only those tools available on Google Play store used for: 1) posting (or tweeting) automatically; 2) scheduling automatic posts or contents; 3) tagging all friends of a sociodigital network in one single content (post, tweet, link or photo); 4) reposting (or retweeting) the same content or message hundreds of times; 5) spamming through private messages (i.e. Facebook inbox); 6) getting or generating automatic “likes” or “follows” for all posts or contents of the same (or similar) account(s); 7) giving automatic “like” or “follow” to similar public pages; and 8) getting lots of “friends” or “followers” by adding accounts or groups massively.

Considering these criteria we built and analyzed a dataset with the top 216 Google Play store automation apps for Facebook, Twitter or Instagram. Later, we used a dataset collected in a previous research to contrast the use of these apps in a case of study: 29 thousand tweets about the last presidential election debate in Argentina (November, 2015). In this last dataset we found which tweets were generated or spread using an automation app, and we matched if the apps detected were part of the top ones in Google Play store.3. Research questions

- What are the most popular automation apps for the main social media platforms according to Google Play recommendations and “similar searches” algorithm?

- Can these automation apps be used as bots for political intends? How?

- What digital practices are involved in the use of these automation apps?

4. Methodology

4.1. First exploration into Google Play StoreWe entered into the Google Play store website and searched for some popular and high-rated automation apps for social media platforms. We used as generic searching criteria “Facebook automation”, “Instagram automation” and “Twitter automation”. Later, we filtered some of the results using more specific searches, such as “automatic” plus “posting”, “sharing” or “liking”, or either “automatic post schedule”, “getting more friends (or followers)” and “automatic re-post (or retweet)”. After checking each one of the obtained results corresponded to an active and functional app, we made a small list of 17 apps considering: a) name of the app (as shown in Google Play); b) application ID (a two part string with both letters and numbers used for product identification); and c) the product´s URL.

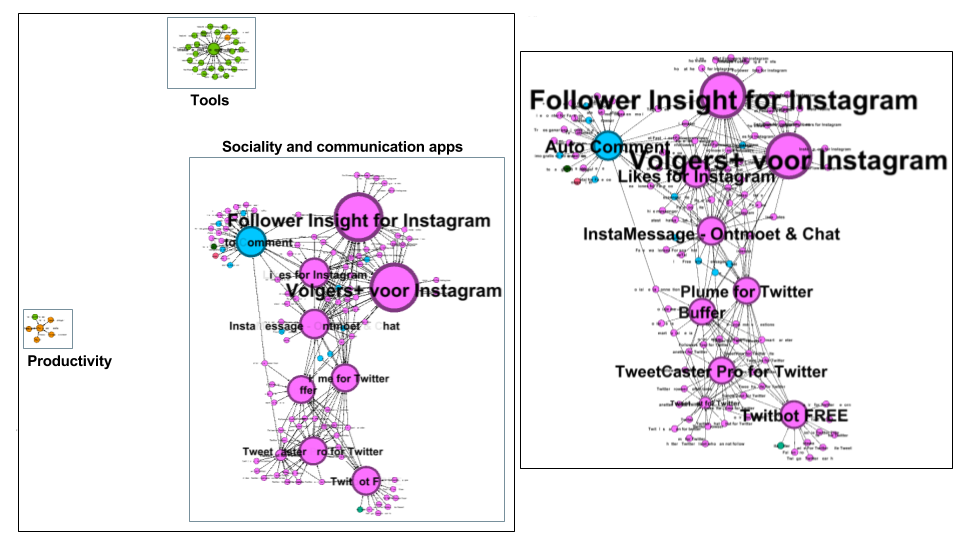

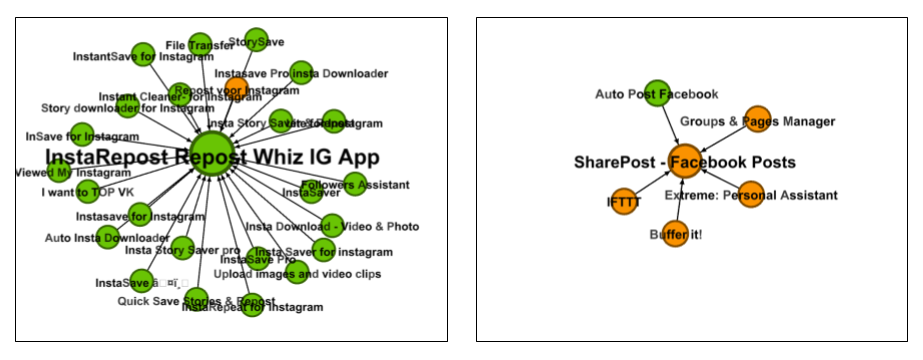

4.2. Building and cleaning the dataset We uploaded this list in the Google Play Similar Apps scraper of the Digital Methods Initiative toolkit. This tool extracted app details for each given product and it also got a new dataset of all the “similar” apps for every token in the list. In total, we found that if we searched in Google Play our original 17 apps list, we would get 478 new ones. However, the resultant dataset needed cleaning and attention. Some of the apps were repeated (for example, showing the American and British version of the same product, or the standard and pro versions). In some other cases, the apps had no assigned metadata (lacked of name, developer, country, etc.), so we tagged them manually. In other cases, metadata was unclear or unreadable (showing signs and numbers instead of letters in the name); we found these anomalies corresponded to apps with names that used non-western characters, like greek, russian or japanese ones, so we substituted the name with a transliteration. After cleaning the database we got only 216 different apps, but all of them acquirable and functional. 4.3. Automation apps network analysis We turned our definitive dataset into a CSV (comma-separated values) table and modeled it like a network using Gephi. There:- We colored the clusters of the similar nodes that were close and tangled together using the same palette, interpreting those were the apps correspondent to similar searches in Google Play store or recommended between each other.

- We categorized each cluster using the apps´ “functions”: sociality, communication, tools, photography and productivity. These categories were part of metadata given by Google Play store.

- We detected the nodes with the highest centrality degree, considering those were the most popular apps (the ones recommended the most by other apps or obtained the most of the times in “similar searches”).

5. Findings

5.1 Google Play store top social media automation appsThe central and most relevant nodes on the similar apps network we generated using Gephi showed that the top Google Play store automation tools are:

- In the sociality category (colored in purple or fuchsia) the American apps Follower Insight and Like for Instagram, as well as the Dutch apps Volgers (Followers) and InstaMessage Ontmoet (Meet) & Chat, also for Instagram. Also, the American tools Plume, TweetCaster, Buffer and Twitbot Free (or Tweetbot) for Twitter.

- In the communication category (in blue) all relevant apps are American, like AutoPost and AutoComment for Facebook.

- In the tools category (in green) the only considerable app is the American InstaRepost Whiz for Instagram.

- And in the productivity (in orange) category stand out the American Share&Post (or SharePost) and Group and Pages Manager apps for Facebook, and IFTTT (initials of If This, Then That) for Twitter.

- There were no results for apps in the photography category. Maybe, because photographic management and edition were not tasks considered in our original automation criteria.

Although the concepts automation software and bot can be used indifferently, the term bot has acquired negative connotations due to its recent malicious purposes. Since the late nineties some bots have interfered users' privacy through address harvesting, while others have worked as malware programs, viruses, worms or zombies (applications without clear metadata or tracking records) used to infect systems and steal information (Morales, Bataineh, Xu & Sandhu, 2010). In the actual context of social media platforms bots can be understood as automatic uploaders of text, links or digital objects, machines to add thousands of friends automatically or apps to increase the impact of a user through massive reviewing, “liking” or commenting (Edwards, Edwards, Spence & Shelton, 2014). Following this logic, after exploring the #ArgentinaDebate dataset we found:

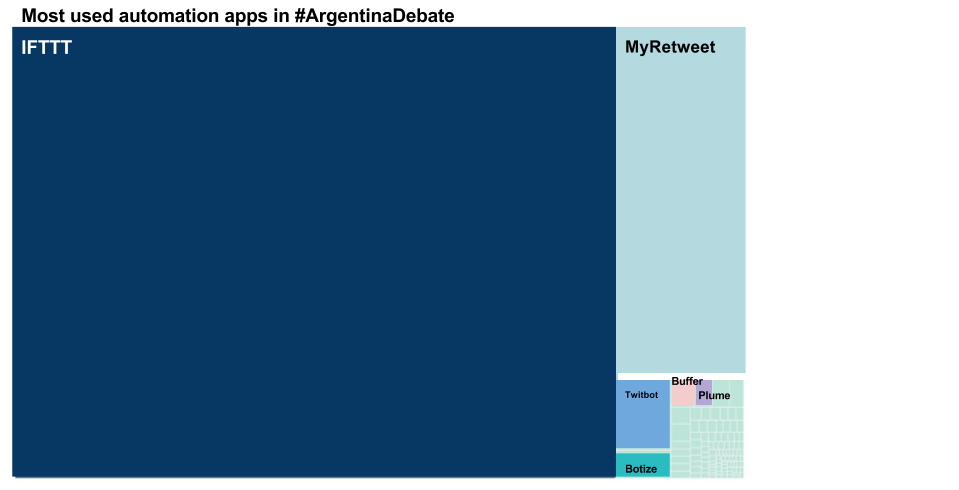

- Almost half of all users that tweeted in the sample used an automation app to boost the reach of their tweets. 13200 out of 29000 accounts did not tweet manually. We found IFTTT was the automation app used the most (in 63% of Twitter bots), while the second (25%) and third (12%) most relevant apps were Myretweet and Botize, respectively.

- Myretweet and Botize are not available on Google Play store, but they are relatively easy to get also in downloadable versions from their main websites.

- It is important to consider that four relevant automation apps in the case of study are currently available on Google Play store: IFTTT, Buffer, Plume and Tweetbot (or Twitbot).

- All these apps are American (excepting Botize, with unknown origin), and most of them are low cost or free.

There is a close relationship between the use of bots and anonymity. The massification of certain positive or negative messages to support or discredit a presidential candidate (speaking about our Argentinian case of study) often implies the concealment of the identity of the author of the texts. We estimated Twitter bots users, in order to avoid tracking or identification, tend to open and manage ghost accounts using fake names and profiles, or showing a real name but looking for a low profile. According to Bryant (2014), a ghost Twitter account is a profile used exclusively for any kind of propaganda, avoiding interaction. After detecting which accounts using bots have a very low rate of followers (zero or close to zero) and a high number of tweets or retweets (more than 50), we introduced some of their users´ names in the online tool Bot-or-not, which analyze the history of every account to get its reliability. Some accounts with a few followers and active tweeting were detected as fake by Bot-or-not.

Recapitulating our methodology and main findings, we developed a methods map with each activity and product, considering: 1) the scraping of Google Play store and assemblage of our first dataset; 2) the analysis of this dataset using a Gephi network and its central nodes; 3) the contrast of the most relevant Google Play store apps (using the “similar searches” criteria) with another dataset (Twitter #ArgentinaDebate tracking); and finally, 4) the study of the relationship between automation apps and ghost accounts.

6. Discussion

6.1. Are bots available in Google Play store for anyone, anywhere?Actually, there are no clear regulations for the use of automation apps (Edlich & Sohoni, 2017). When someone downloads any kind of social media app on Google Play store there are no agreements detailing the possible purposes behind the uses of these apps, nor any special rules or consent policies. After exploring the Google Play store case we found automation apps are available to any person and public (without filters in the platform), however, the download tendencies are different for every social media user and app:

- All apps related to Facebook are mainly in the social and communication categories and are often used to get the most “friends” or “likes” as possible. Google Play store, as we said before, recommend AutoPost and AutoLike.

- Apps related to Twitter can be also found in the communication category, but they are not only used to get the highest number of “followers” or “followed” as possible. Other important uses are the schedule of automatic posts (using apps as Plume or Botize) and the massive “retweeting” or “reposting” (using, for example, Tweetbot or TweetCaster). Some apps give all these services at the same time, as IFTTT, which can be found in production category and is also one of the most recommended.

- In this study we found through a network analysis the relevance of some Dutch apps like Volgers or Ontmoet (the Dutch version of InstaMessage). Maybe these results are a consequence of doing the study in the Netherlands, considering the IP address detected by the Google Play store web could impact in the way this service manages searches and results. To corroborate the true relevance of the Dutch or European apps found we should repeat the study later, elsewhere.

After exploring which are the companies that develop the highest number of automation apps we discovered some paths for a future study to trace the economy of easy-access bots. The top producers of these apps are large Internet enterprises like Google or UberMedia, along with important social media platforms like Facebook, WhatsApp or Instagram. It could be supposed that the design of bots come mainly from small or clandestine companies, but the same programmers of the largest web services are the ones behind automation apps, offering them for free as part of their downloadable tools. Just in the case of Twitter the most relevant apps are not closely related to the company managing the platform. Nevertheless, the Twitter apps market has empowered medium-size companies such as IFTTT, Botize or Hootsuite too, which have grown considerably in the last five years due to their automation services, and can be easily found on the web. In our #ArgentinaDebate dataset (29000 tweets) IFTTT is the most relevant app, covering almost 52% of the market (132000 tweets), but to assert this is the top automation app used in Twitter nowadays, we would need more cases of study.

6.3. Some practices involving social media bots in politicsThere were an important number of ghost Twitter users in the #ArgentinaDebate dataset we explored, so we may suppose the use of bots is a popular practice in politics, at least in Latin American cases. Not all the users that support their candidate´s promotion through automatic “tweeting” or “following” were considered as bots in our study. We considered all the non-anonymous users as legitimate citizens on Twitter and we only defined as bots those users with a ghost or anonymous account who were incorporating automation apps to their communication and political practices. In the case of Argentinian presidential debate almost a third part of our whole dataset were tweets produced by bots. Besides, these bots were diverse in their affinity to ideologies or parties, so it is possible to think politics are strongly influenced by automation in general, and all candidates and factions look to get more sympathizers in Twitter through the recruitment of ghost and automatized users.

6.4. Some reflections on a new typology of social media automation usersAfter analyzing briefly the behavior of some bots detected in #ArgentinaDebate dataset we could propose a draft for a new typology of social media bots and automation apps users:

- Artificial intelligence ghost users (or pure artificial bots). Credible, attractive, competent and interactional programs that simulate human posting, reposting or commenting through an artificial intelligence applied to a fake account (zero “followers” and “following” and a high rate of activity).

- Artificial intelligence bots related to a public person or institution (or corporative use bots). Interactional programs that simulate human social media activities, but in the name of a company, political party, public figure or any marketing or technical support service.

- Automated human accounts (or just automated tweeters, facebookers, instagramers, etc.). Non-anonymous people that use easy-access (either commercial or free) automation apps to optimize their social media practices (for example in Facebook, posting, reposting, finding friends, adding friends, inbox messaging, etc.).

- Automated ghost-human users (or human-bots). Anonymous users with zero (or close to zero) “followers” (or “friends”) and “following” that use any automation app to optimize social media practices to support or discredit a political or public figure, to enforce or ridicule an activist or political cause, to promote a marketing plan, company or product, or to massify any kind of content.

- Nonsense or offensive ghost automated users (or trolls). Fake accounts that use automation apps just to send messages without any other purpose than bullying or offending a certain user or group of users (“trolling”).

As part of the Methods Maps: Visualizing automation project of the Digital Methods Summer School 2017 at University of Amsterdam, we did not only identified and analyzed bots and automation apps in social media platforms, but also designed a digital methods map to make our study replicable in the future. The objective of our methods map is to give other scholars the opportunity to research automation tools in different temporary and geographic contexts in the future. We only focused on apps available on Google Play store and in an Argentinian political event in Twitter, but anyone could modify or amplify our methods map proposal to study different apps stores, cases of study or agendas, and social media platforms. Additionally, future researchers can use more than one cases of study or platforms, as well as other digital methods different than ours, adding new statistic or cultural analytics programs to our network analysis in Gephi, or diverse visualizations to our Tableau graphics. We only recommend to be careful during the construction and cleaning of the datasets and to explore and test all the considered methods or platforms before doing the final research.

7. Conclusion

Our evidence suggests that automation has been important in some common practices on social media platforms, especially on those related to political events. Automation apps are not difficult to find, and there are more than 200 available on Google Play store for free or at a low cost. The market around automation apps is so relevant for Internet economy that some of the main tools developers are the largest bussiness that provide web services, such as Google or UberMedia, while other outstanding developers are big social media companies like Facebook or Instagram. Twitter is not a significant designer of automation apps itself, but has allowed the activity and growth of many companies that develop and distribute these apps through websites, such as IFTTT, Botize or Plume. Also, there are many automation tools for Twitter on Google Play store, and all these, just like the ones available on the web, are often used by ghost accounts to schedule messages or activities, to spread a message massively, or to get social or political relevance. Automation has to be pointed out in future researching on the political and cultural uses of social media, taking into account there are no actual or clear regulations on the production, commerce or use of bots, and that many social media or marketing platforms are gaining advantage from this lack of transparence. Some considerations have still to be discussed for further studies, like if bots can be either artificial, corporative or human, because at least in this project, they seem to produce the same or very similar performative effects.

8. References

Borra, E., Rieder, B. (2014). Programmed method: developing a toolset for capturing and analyzing tweets. Aslib Journal of information management, 66 (3). DOI: 10.1108/AJIM-09-2013-0094 Bryant, C. (2014). Top 5 Ghost Twitters. Tech?. http://computer.howstuffworks.com/internet/social-networking/information/5-ghost-twitters.htm Retrieved July 18 2017. Chu, Z., Gianvecchio, S., Wang, H., Jajodia, S. (2012). Detecting automation of Twitter accounts: Are you a human, bot or cyborg? IEEE Transactions on dependable and secure computing, 9 (6). DOI: 10.1109/TDSC.2012.75 Edlich, A., Sohoni, V. (2017). Burned by the bots. Why robotic automation is stumbling? McKinsey and Company. http://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/digital-mckinsey/our-insights/digital-blog/burned-by-the-bots-why-robotic-automation-is-stumbling Retrieved July 24 2017. Edwards, C., Edwards, A., Spence, P., Shelton, A. (2014). Is that bot running the social media feed? Testing the differences in perceptions of communication quality for a human agent and a bot agent on Twitter. Computer in human behavior, 33(1). DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.08.013 Dunham, K., Melnick, J. (2008). Malicious bots. An inside look into the cyber-criminal underground of the Internet. Florida: CRC Press. Kollanyi, B., Howard, P., Wooley, S. (2016). Bots and automation over Twitter during the third presidential debate. Data Memo 2016.3. The Computational Propaganda Project. Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford. http://comprop.oii.ox.ac.uk/2016/10/31/bots-and-automation-over-twitter-during-the-third-u-s-presidential-debate/ Retrieved July 17 2017. Morales, J.A., Bataineh, A., Xu, S., Sandhu, R. (2010). Analyzing and exploiting network behaviors of malware. Lecture paper. International conference on security and privacy in communication systems. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-16161 Warren, C. (2013). Google Play hits 1 million apps. Mashable. http://mashable.com/2013/07/24/google-play-1-million/#6hwczhJ56iqb Retrieved July 17 2017. Zeifman, I. (2017). Bot traffic report 2016. Imperva Incapsula https://www.incapsula.com/blog/bot-traffic-report-2016.html Retrieved July 17 2017.Topic revision: 01 Nov 2017, EloyCalocaLafont

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors. Ideas, requests, problems regarding Foswiki? Send feedback